Ghost World

I'm going to avoid the obvious comparison for this film because it makes me feel like I'm doing it a disservice. I suppose it's a cult film of a sort, but even so Ghost World seems to be much overlooked, even by those who like a bit of late teenage direction/existential-angst. It's ambitions may not be extraordinary, but the film is a wonderfully sharp and well formed piece. It's very well acted, funny and compassionate, but I always thought the ending was also very depressing. Didn't find that quite so much this time, but there's still something to my previous opinion.

The only small thing that does get to me is that the film displays hollywood's inability to cast physically unattractive actresses. Not that there is anything in the story that implies Enid should be, but I'd still like to see how it would play out if she was not so nice to look at.

Little Miss Sunshine

I've seen Little Miss Sunshine twice before from never quite all the way from the beginning. I've also not seen it with Amy laughing her head of at bits of the film. I've never seen someone laugh so much at a horn before. Makes an excellent film even better.

Slight qualm on reflection: is the mother in the film anything more than the conventional harassed but determined and loving mother character?

Aguirre, Wrath of God

On an entirely different note, Werner Herzog's film is a bit like Apocalypse Now if it was set in South America, with Conquistadors rather than Americans and dubbed into German. Klaus Kinski as the self-destructive Aguirre sways about unnervingly, looking at people as if he's sizing up the best place to stab them. I can see its considerable merits - minimalist storytelling, a lush and unrelenting backdrop, a psychotic sense of inevitability, so-on. It reminded me of a shakespeare play at times, even though it's far from wordy; something about the pace of events, the arrangement of characters and the tragic narrative format.

Despite all that, for some reason the film didn't quite click with me. Maybe the "civilised people go mad in jungle" is a little passé, or maybe you just need to be in the right frame of mind. Also I was a little distracted by the how the guy playing the priest looked and acted just like Julian Barrat.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

Sunday, September 5, 2010

Quick Film Reviews #1

Cross-posting some old posts, because I feel like it.

Duck Soup

It's probably lost a little over time, but Groucho's wit is sharp, and even the clowning raises some laughs. Entertaining enough to watch in its own right, but ideal if you want to know what the Marx brothers were all about.

Weekend

I raved a bit about this film before. If you want a film that doesn't necessarily make much sense or have any real plot, but batters you with ideas and with hatred for the bourgeois, this is for you. Even if you don't think that's what you want, you should watch it anyway.

The France of Godard's week end is a place where people are united only in despising one another, in a countryside covered in wrecked and burnt-out cars. Middle class are callous, shrill, greedy, murderous, working class are static, ambling, dull, materialistic. Godard's only sympathy seems to lie with revolutionary theory. If the cannibalistic, hippy "Seine-Oise Liberation Front" are an example of it in practice, then of the liberating effects of violence (chez Fanon) are not what was hoped for.

Weekend is a looking glass reflecting colonial violence back into the heart of France, as its characters reference torturing in Algeria or fighting in Ethiopia.

Princess Monononoke

The story goes that the US distributors bought Princess Mononononoke thinking they were getting a nice twee film from "the Japanese Disney", then didn't know what to do with it. It is certainly the most adult of the Studio Ghibli films I've seen - none of the others have a man getting his arms shot off in the first fifteen minutes. I've seen it a few times now, and what struck me last time was just how complex it is. The basic plot isn't particularly difficult to follow, but the number of factions, none of whom have clear-cut morals or motivations, is impressive by any standards. There is magic, but there are no magic solutions in this world, just people learning and struggling to get along.

OldBoy

It was good, but I I was a little underwhelmed. A bit melodramatic (in a negative way), I guessed a couple of the twists (and I'm very bad at guessing twists) and an ending which, while not quite deus ex machina is at least somewhat unsatisfying. The most memorable scene may be the protracted fight along the length of a corridor. It's not a masterwork of martial arts choreography nor a study in painful and bloody realism, but in the confined space it has a wonderful linear progression that's very aesthetically pleasing.

Duck Soup

It's probably lost a little over time, but Groucho's wit is sharp, and even the clowning raises some laughs. Entertaining enough to watch in its own right, but ideal if you want to know what the Marx brothers were all about.

Weekend

I raved a bit about this film before. If you want a film that doesn't necessarily make much sense or have any real plot, but batters you with ideas and with hatred for the bourgeois, this is for you. Even if you don't think that's what you want, you should watch it anyway.

The France of Godard's week end is a place where people are united only in despising one another, in a countryside covered in wrecked and burnt-out cars. Middle class are callous, shrill, greedy, murderous, working class are static, ambling, dull, materialistic. Godard's only sympathy seems to lie with revolutionary theory. If the cannibalistic, hippy "Seine-Oise Liberation Front" are an example of it in practice, then of the liberating effects of violence (chez Fanon) are not what was hoped for.

Weekend is a looking glass reflecting colonial violence back into the heart of France, as its characters reference torturing in Algeria or fighting in Ethiopia.

Princess Monononoke

The story goes that the US distributors bought Princess Mononononoke thinking they were getting a nice twee film from "the Japanese Disney", then didn't know what to do with it. It is certainly the most adult of the Studio Ghibli films I've seen - none of the others have a man getting his arms shot off in the first fifteen minutes. I've seen it a few times now, and what struck me last time was just how complex it is. The basic plot isn't particularly difficult to follow, but the number of factions, none of whom have clear-cut morals or motivations, is impressive by any standards. There is magic, but there are no magic solutions in this world, just people learning and struggling to get along.

OldBoy

It was good, but I I was a little underwhelmed. A bit melodramatic (in a negative way), I guessed a couple of the twists (and I'm very bad at guessing twists) and an ending which, while not quite deus ex machina is at least somewhat unsatisfying. The most memorable scene may be the protracted fight along the length of a corridor. It's not a masterwork of martial arts choreography nor a study in painful and bloody realism, but in the confined space it has a wonderful linear progression that's very aesthetically pleasing.

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

Death on the High Seas

As the refrain goes, it's not clear exactly what went on when Israeli commandos boarded convoy of aid ships, starting a confrontation in which 10 people were killed (though none of the commandos). Probably the Israeli military knows what happened, provided their troops aren't incompetent or covering up. It might take a wikileaks-style full-length video to give everyone else the chance to make up their minds. I think what I've written here is appropriate to most of the likely events, but it could be invalidated by an extreme truth, from either 'side' of the debate.

Whatever their motivations and whether or not they were foolhardy, I can't help admiring the bravery of those who resisted the boarding action. You're transporting a cargo of aid to Gaza, making a political statement against the blockade. You know the Israeli military is out to stop you. You're going to challenge just how far they will go to stop you. As long as you're in international waters the legalities are, to say the least, disputed.

When they board you in the middle of the night, you know they're going to, at the least, hijack your ship and detain you. If you want to stop them it comes down to a matter of force. And as any freighter captain sailing off the horn of Africa will tell you, the best way to repel boarders is as soon as possible. Catapults and whatever weapons you can improvise versus machine guns. These people must have known what to expect in a fight; expected the Israeli commandos to respond with deadly force.

They weren't attacking civilians and they weren't blowing up soldiers from afar. They were fighting face-to-face with soldiers trying to board their ship in international waters. Unprepared soldiers, perhaps, but still fully-armed soldiers.

I think the fundamental Israel's 'bungling' is making this basic miscalculation - they expected people to back down when faced with superior force and deadly violence. Instead they found people unafraid to fight back against the odds.

I can't shake the feeling it's like a strangely inverted Cuban Missile Crisis, with a catastrophic loss of moral and political standing instead of a nuclear war as the consequence of intercepting the ships.

Whatever their motivations and whether or not they were foolhardy, I can't help admiring the bravery of those who resisted the boarding action. You're transporting a cargo of aid to Gaza, making a political statement against the blockade. You know the Israeli military is out to stop you. You're going to challenge just how far they will go to stop you. As long as you're in international waters the legalities are, to say the least, disputed.

When they board you in the middle of the night, you know they're going to, at the least, hijack your ship and detain you. If you want to stop them it comes down to a matter of force. And as any freighter captain sailing off the horn of Africa will tell you, the best way to repel boarders is as soon as possible. Catapults and whatever weapons you can improvise versus machine guns. These people must have known what to expect in a fight; expected the Israeli commandos to respond with deadly force.

They weren't attacking civilians and they weren't blowing up soldiers from afar. They were fighting face-to-face with soldiers trying to board their ship in international waters. Unprepared soldiers, perhaps, but still fully-armed soldiers.

I think the fundamental Israel's 'bungling' is making this basic miscalculation - they expected people to back down when faced with superior force and deadly violence. Instead they found people unafraid to fight back against the odds.

I can't shake the feeling it's like a strangely inverted Cuban Missile Crisis, with a catastrophic loss of moral and political standing instead of a nuclear war as the consequence of intercepting the ships.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Strike!

It's a common complaint of employers that firing or laying people off, even when there is a very good reason for it, is far too difficult and bureaucratic a process.

What I never appreciated was that this works in the other direction, too. The High Court has granted the third injunction in six months to prevent BA workers striking. Now it could be the case that Unite are incompetent. That's possible, even though you'd think that if there's one thing a union should make sure it's good at doing, it's calling a strike.

I suspect that this will come as no surprise to anyone politically aware during the Thatcher-era, that the rules for calling a strike are as challenging as any that employers face.

What I never appreciated was that this works in the other direction, too. The High Court has granted the third injunction in six months to prevent BA workers striking. Now it could be the case that Unite are incompetent. That's possible, even though you'd think that if there's one thing a union should make sure it's good at doing, it's calling a strike.

I suspect that this will come as no surprise to anyone politically aware during the Thatcher-era, that the rules for calling a strike are as challenging as any that employers face.

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

a diversified party system = a diversified media

I'm not a serious media-watcher, but it's hard to miss large sections of the media blowing their shit, first about the Nazi LibDems and now about the LibDem-Conservative coalition.

We expect this from the ever-angry Mail, suddenly finding some new important things to hate. However in general it upsets the media ecosystem. In the UK we have some newspapers that reliably back a particular party - the Torygraph and the Mirror, for example. This election has already shifted that system, when the Guardian belatedly came out in support of the Liberal Democrats rather than Labour. Then there are the Murdoch papers that throw their impressive weight behind one party.

Coalition government make these simple media positions hard to sustain. Not only that, but I would propose that a more diverse party system, such as the one we may well be edging towards, means a more diversified media. Each significant party means a target market of supporters looking for news and comment. Is a media conglomerate like Murdoch's flexible enough to support a number of different parties? At the very least, this seems to diffuse its influence. It may force a genuinely more diverse editorial line.

On top of that this kind of change would open opportunities for new media. British newspapers are financially and professionally troubled enough as it is.

So, if and when electoral reform approaches, expect a media campaign against it as vicious as any we've seen. Coalition government and a diversified party system is not in the interest of big media corporations.

We expect this from the ever-angry Mail, suddenly finding some new important things to hate. However in general it upsets the media ecosystem. In the UK we have some newspapers that reliably back a particular party - the Torygraph and the Mirror, for example. This election has already shifted that system, when the Guardian belatedly came out in support of the Liberal Democrats rather than Labour. Then there are the Murdoch papers that throw their impressive weight behind one party.

Coalition government make these simple media positions hard to sustain. Not only that, but I would propose that a more diverse party system, such as the one we may well be edging towards, means a more diversified media. Each significant party means a target market of supporters looking for news and comment. Is a media conglomerate like Murdoch's flexible enough to support a number of different parties? At the very least, this seems to diffuse its influence. It may force a genuinely more diverse editorial line.

On top of that this kind of change would open opportunities for new media. British newspapers are financially and professionally troubled enough as it is.

So, if and when electoral reform approaches, expect a media campaign against it as vicious as any we've seen. Coalition government and a diversified party system is not in the interest of big media corporations.

Sunday, May 9, 2010

Whatever happened to our liberal dream?

So, after all the talk of a path-breaking election, a new dawn for the liberal democrats, independents and small parties, what we get is the opposite. Despite a seat gained by the Green Party, independents and small parties have gone from three to two seats. Nationalist parties have remained much the same.

And the result looks like a terrible disappointment for the Liberal Democrats, losing five seats - almost 10% of their total. Their share of the vote went up by a meagre 1%, meaning they were more than usually screwed by the electoral system. But a significant jump in LibDem votes would have made a good jumping off point for reform.

To round off the disappointment, the combined total of Labour and LibDem MPs is 11 short of a majority. Even with Plaid Cymru and SNP votes, a coalition would still be two short.

So the LibDems are left trying to come to an agreement with the Conservatives, and not from a position of strength. A failure to agree a workable coalition would itself be a big setback for LibDem dreams of proportional representation, which almost always requires coalition governments. David Cameron needs to offer enough for the Liberal Democrat Party to vote in favour and to stop the party from sabotaging the coalition at some point in the future, and forcing a new election (not that this would necessarily be bad for the Tories). (Apparently LibDem agreement to a coalition would require 75% of the votes of MPs and 75% of the Federal Executive, or 2/3 of Voting Representatives.)

We'll find out soon enough what Cameron has offered, so there's not much point speculating. While the Conservative Party and the LibDems can certainly find common ground, it's unlikely that the Conservative Party would accept any major electoral reform though. (In the short-run it almost certainly means a solid Labour-LibDem majority.) Of course, the LibDems have been messed around on electoral reform before, after their electoral pacts with Labour. Labour haven't even managed to properly reform the House of Lords.

A House of Lords mainly elected by PR (or some alternative voting system) might be acceptable to the Conservatives, but could be a poison pill for the Liberal Democrats, stalling any further reform. Having both an upper and lower chamber selected in the same fashion is not a very good idea, so to get a reformed Commons would mean making another change to the Lords.

An all-party commission on electoral reform, along with a binding agreement to follow its recommendations, may be the best the Lib Dems can hope for. That commission may be hard-pressed to report before the next election (on the basis that the next election could be quite soon).

Failing that, what concessions could Cameron make to entice the Liberal Democrats without offering any significant electoral reform? That could be interesting to see; the Liberal Democrats getting their way on lots of other issues, but not on electoral reform.

And the result looks like a terrible disappointment for the Liberal Democrats, losing five seats - almost 10% of their total. Their share of the vote went up by a meagre 1%, meaning they were more than usually screwed by the electoral system. But a significant jump in LibDem votes would have made a good jumping off point for reform.

To round off the disappointment, the combined total of Labour and LibDem MPs is 11 short of a majority. Even with Plaid Cymru and SNP votes, a coalition would still be two short.

So the LibDems are left trying to come to an agreement with the Conservatives, and not from a position of strength. A failure to agree a workable coalition would itself be a big setback for LibDem dreams of proportional representation, which almost always requires coalition governments. David Cameron needs to offer enough for the Liberal Democrat Party to vote in favour and to stop the party from sabotaging the coalition at some point in the future, and forcing a new election (not that this would necessarily be bad for the Tories). (Apparently LibDem agreement to a coalition would require 75% of the votes of MPs and 75% of the Federal Executive, or 2/3 of Voting Representatives.)

We'll find out soon enough what Cameron has offered, so there's not much point speculating. While the Conservative Party and the LibDems can certainly find common ground, it's unlikely that the Conservative Party would accept any major electoral reform though. (In the short-run it almost certainly means a solid Labour-LibDem majority.) Of course, the LibDems have been messed around on electoral reform before, after their electoral pacts with Labour. Labour haven't even managed to properly reform the House of Lords.

A House of Lords mainly elected by PR (or some alternative voting system) might be acceptable to the Conservatives, but could be a poison pill for the Liberal Democrats, stalling any further reform. Having both an upper and lower chamber selected in the same fashion is not a very good idea, so to get a reformed Commons would mean making another change to the Lords.

An all-party commission on electoral reform, along with a binding agreement to follow its recommendations, may be the best the Lib Dems can hope for. That commission may be hard-pressed to report before the next election (on the basis that the next election could be quite soon).

Failing that, what concessions could Cameron make to entice the Liberal Democrats without offering any significant electoral reform? That could be interesting to see; the Liberal Democrats getting their way on lots of other issues, but not on electoral reform.

Friday, April 16, 2010

Bible Stories Part 1: Genesis

Sensibly, the Council of Nicea decided to put the most famous book in the Bible at the front. If they had started off with something like Joel, people could well have been put off.

The Biblical creation myth may be unusual in being quite straightforward. There are no ravens dropping rocks into the ocean, gods spitting out their semen or wars with the titans. There's just God, who makes stuff, in a particular order, is happy with it, then has a rest. Of course, God has made the first of many misjudgements with regards to his favourite creatures. It's never clear whether God is struggling to understand humanity or whether he's wilfully ignoring how his creations really think.

The story of the fall is obviously much debated, but the story of Cain and Abel is itself rather mysterious. It's not clear why God rejects Cain's offering, prompting him to murder his brother. My guess was that it is a myth related to struggles between arable farmers and herders, something that the wikipedia article confirms may be the case. Certainly there is a continued emphasis on livestock herding/farming over arable, and on animals over crops in sacrifice. Cain and Abel is just the first of a number of little stories that seem half-formed. They leave you wondering whether there's context we're missing, there are/were alternate versions, it would have made sense to people at the time, or whether the story or event was always a fragment.

Genesis itself is a series of tales that seem remarkably amoral. They're a bit like the tales of Ancient Greeks (the ones without mythical beasts), but without the flair. You get a few principles - don't murder your brother, don't sleep with other people's wives, be generous to guests and most of all, look after your family (but your daughters are less important than guests), and most of all, do what God says - but on the whole that's not what it's about.

The concluding story of Joseph is definitely the most complete and conventionally structured narrative. Joseph is also a rare sympathetic character in the first few books of the Bible. It's no wonder the story got translated into the most divine of art-forms, the musical. An interesting little tidbit from the story of Joseph is that he didn't just dole out food during the famine, he made Egyptians pay for it, so that by the end of the seven years the people of Egypt had sold all their lands and possessions, and were left as slaves to the Pharaoh.

In Genesis you start to see some of the characteristics of God that are less commonly remarked upon. We all know he's a mighty god, a jealous god, but he's also a very forgetful god. Despite insisting on all manner of signs of the covenant between himself and the descendants of Abraham, he still needs to be regularly reminded of what he promised. I get the feeling that had he not made the rainbow as a reminder of his promise never to destroy life on earth again, he really would forget. I suppose at least in this case he knows his problems, like the person who leaves post-it notes everywhere. He also has a bit of an obsession with foreskins.

The Biblical creation myth may be unusual in being quite straightforward. There are no ravens dropping rocks into the ocean, gods spitting out their semen or wars with the titans. There's just God, who makes stuff, in a particular order, is happy with it, then has a rest. Of course, God has made the first of many misjudgements with regards to his favourite creatures. It's never clear whether God is struggling to understand humanity or whether he's wilfully ignoring how his creations really think.

The story of the fall is obviously much debated, but the story of Cain and Abel is itself rather mysterious. It's not clear why God rejects Cain's offering, prompting him to murder his brother. My guess was that it is a myth related to struggles between arable farmers and herders, something that the wikipedia article confirms may be the case. Certainly there is a continued emphasis on livestock herding/farming over arable, and on animals over crops in sacrifice. Cain and Abel is just the first of a number of little stories that seem half-formed. They leave you wondering whether there's context we're missing, there are/were alternate versions, it would have made sense to people at the time, or whether the story or event was always a fragment.

Genesis itself is a series of tales that seem remarkably amoral. They're a bit like the tales of Ancient Greeks (the ones without mythical beasts), but without the flair. You get a few principles - don't murder your brother, don't sleep with other people's wives, be generous to guests and most of all, look after your family (but your daughters are less important than guests), and most of all, do what God says - but on the whole that's not what it's about.

The concluding story of Joseph is definitely the most complete and conventionally structured narrative. Joseph is also a rare sympathetic character in the first few books of the Bible. It's no wonder the story got translated into the most divine of art-forms, the musical. An interesting little tidbit from the story of Joseph is that he didn't just dole out food during the famine, he made Egyptians pay for it, so that by the end of the seven years the people of Egypt had sold all their lands and possessions, and were left as slaves to the Pharaoh.

In Genesis you start to see some of the characteristics of God that are less commonly remarked upon. We all know he's a mighty god, a jealous god, but he's also a very forgetful god. Despite insisting on all manner of signs of the covenant between himself and the descendants of Abraham, he still needs to be regularly reminded of what he promised. I get the feeling that had he not made the rainbow as a reminder of his promise never to destroy life on earth again, he really would forget. I suppose at least in this case he knows his problems, like the person who leaves post-it notes everywhere. He also has a bit of an obsession with foreskins.

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Quick Book Reviews #1

Posting some old stuff here to get a bit of momentum

The Economic Naturalist: Why economics explains almost everything by Robert H Frank

Robert Frank has found the most economical way to write a book, which is to copy a load of his students' essays. The Economic Naturalist is a great introduction to the basic principles of economics, from the basic proposition that a person does something if the perceived benefits outweigh the costs to tragedies of the commons to marketplace signals. From experience, Frank's argument that economics is taught badly - with too few practical applications and too little attention to the basics - is true. If you want an easy to read, and easy to dip in and out of, economics primer, this is a good choice.

Having studied some economics, I was familiar with large parts of the book, but it gave me a better grounding and some portions - particularly the section on discount pricing - were interesting and largely new to me.

On the downside, it's also a good illustration of some problems with basic economics. The answer to the question "can economics explain everything?" appears to be yes, as long as you expand "economics" to include just anything else you think is relevant. At least one of the answers in the book doesn't actually invoke any economics, while others beg the question. Sometimes it seems like the economics is explaining the easy bit.

Quite a few of the answers given in the book are also very dubious, and almost all are unsupported by any empirical research or evaluation of alternative explanations. Saying that economics is an excellent way of quickly generating plausible hypotheses about things is less catchy but a lot more plausible than that it explains everything. How accurate these hypotheses are is open to question.

Collapse: why societies choose to succeed or fail by Jared Diamond

Jared Diamond is a biologist-cum-anthropologist-cum-scientifically-minded-historian/archaeologist and Collapse is his attempt to demonstrate that environmental factors can and do cause societies to collapse, and to learn some lessons from this. Diamond's a good, and persuasive author, but still I wasn't massively struck by this book. Maybe I'm not a good audience for it, as I don't take much persuading. Even so, Diamond's scientific instincts to pile on the evidence, from every kind of nologist could try the patience. There's a similar issue with Guns, Germs and Steel, where the last third largely goes over evidence when you've already been convinced by the first two thirds.

Collapse is interesting in some ways. For example, Diamond doesn't come down on the side of either top-down or bottom-up solutions. They both have their places. What's particularly important is that people can't escape the results of their actions. He is positive about the potential for corporations, with appropriate pressure, to be environmentally responsible. Also, did you know Vikings were afflicted by goat-scorn? Or, more seriously, that despite being starved (literally) for agricultural and hunting resources, Greenland Norse didn't eat fish.

One quote I was particularly taken by is about how the Japanese, who had big problems with deforestation, solved their problems with the resources at hand. That is an important lesson, that you can't rely on the development or invention of new resources. It brings up the role of technology, which Diamond is very skeptical of. After increasing our environmental impact for centuries (millenia even), what are the chances technological developments will suddenly start reducing it? At the very least, we need to have a strong degree of skepticism about the impacts of more environmentally safe technologies, particularly when they involve large-scale implementation costs. At the same time, technological change is one of the strongest forces in our society. Can we not treat it as a resource, which can be directed in different ways, albeit to somewhat uncertain outcomes?

Diamond emphasises that little is inevitable, and societies choose their path. He is "cautiously optimistic" about our prospects for dealing with environmental problems, but I can't help feeling that you can't write a successful book if you're not. In particular, it's not clear to what degree key decision-makers can isolate themselves from negative changes - if nothing else, because many of those changes happen slowly. We also suffer from a serious problem of "creeping normalcy", which makes it hard to deal with gradual and stochastic (variable, climate-style) changes. Fortunately, right at the back there's a picture of Jared Diamond looking incredibly friendly and curmudgeonly, to comfort you if you're feeling a bit depressed by it all.

Watchmen, story by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

Seeing that the film is out, I thought "it's about time I read the graphic novel", although I couldn't read it in public because then everyone would think I wasn't cool. I won't add much to everything else that's been written about this comic, but it certainly is an acute and extraordinary piece of work. I'm not sure about the odd thing - I'm not sure the climax fits perfectly and there's a parallel comic story that's I don't entirely get. Some characters are more interesting than others, but that's inevitable when some of them are so interesting.

Amazon has the first few pages to read here.

If you've any interest in super heroes, popular culture, mutually assured destruction, morality, society, people, or just about anything else, then you should probably read Watchmen.

Postscript: I was talking to Mark the other week about the difference between the ending of the Watchmen film and comic. On the one hand, the ending of the film is significantly less mental. But on the other, it does significantly change the connotations of the ending. Which is more appropriate I couldn't say.

The Economic Naturalist: Why economics explains almost everything by Robert H Frank

Robert Frank has found the most economical way to write a book, which is to copy a load of his students' essays. The Economic Naturalist is a great introduction to the basic principles of economics, from the basic proposition that a person does something if the perceived benefits outweigh the costs to tragedies of the commons to marketplace signals. From experience, Frank's argument that economics is taught badly - with too few practical applications and too little attention to the basics - is true. If you want an easy to read, and easy to dip in and out of, economics primer, this is a good choice.

Having studied some economics, I was familiar with large parts of the book, but it gave me a better grounding and some portions - particularly the section on discount pricing - were interesting and largely new to me.

On the downside, it's also a good illustration of some problems with basic economics. The answer to the question "can economics explain everything?" appears to be yes, as long as you expand "economics" to include just anything else you think is relevant. At least one of the answers in the book doesn't actually invoke any economics, while others beg the question. Sometimes it seems like the economics is explaining the easy bit.

Quite a few of the answers given in the book are also very dubious, and almost all are unsupported by any empirical research or evaluation of alternative explanations. Saying that economics is an excellent way of quickly generating plausible hypotheses about things is less catchy but a lot more plausible than that it explains everything. How accurate these hypotheses are is open to question.

Collapse: why societies choose to succeed or fail by Jared Diamond

Jared Diamond is a biologist-cum-anthropologist-cum-scientifically-minded-historian/archaeologist and Collapse is his attempt to demonstrate that environmental factors can and do cause societies to collapse, and to learn some lessons from this. Diamond's a good, and persuasive author, but still I wasn't massively struck by this book. Maybe I'm not a good audience for it, as I don't take much persuading. Even so, Diamond's scientific instincts to pile on the evidence, from every kind of nologist could try the patience. There's a similar issue with Guns, Germs and Steel, where the last third largely goes over evidence when you've already been convinced by the first two thirds.

Collapse is interesting in some ways. For example, Diamond doesn't come down on the side of either top-down or bottom-up solutions. They both have their places. What's particularly important is that people can't escape the results of their actions. He is positive about the potential for corporations, with appropriate pressure, to be environmentally responsible. Also, did you know Vikings were afflicted by goat-scorn? Or, more seriously, that despite being starved (literally) for agricultural and hunting resources, Greenland Norse didn't eat fish.

One quote I was particularly taken by is about how the Japanese, who had big problems with deforestation, solved their problems with the resources at hand. That is an important lesson, that you can't rely on the development or invention of new resources. It brings up the role of technology, which Diamond is very skeptical of. After increasing our environmental impact for centuries (millenia even), what are the chances technological developments will suddenly start reducing it? At the very least, we need to have a strong degree of skepticism about the impacts of more environmentally safe technologies, particularly when they involve large-scale implementation costs. At the same time, technological change is one of the strongest forces in our society. Can we not treat it as a resource, which can be directed in different ways, albeit to somewhat uncertain outcomes?

Diamond emphasises that little is inevitable, and societies choose their path. He is "cautiously optimistic" about our prospects for dealing with environmental problems, but I can't help feeling that you can't write a successful book if you're not. In particular, it's not clear to what degree key decision-makers can isolate themselves from negative changes - if nothing else, because many of those changes happen slowly. We also suffer from a serious problem of "creeping normalcy", which makes it hard to deal with gradual and stochastic (variable, climate-style) changes. Fortunately, right at the back there's a picture of Jared Diamond looking incredibly friendly and curmudgeonly, to comfort you if you're feeling a bit depressed by it all.

Watchmen, story by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

Seeing that the film is out, I thought "it's about time I read the graphic novel", although I couldn't read it in public because then everyone would think I wasn't cool. I won't add much to everything else that's been written about this comic, but it certainly is an acute and extraordinary piece of work. I'm not sure about the odd thing - I'm not sure the climax fits perfectly and there's a parallel comic story that's I don't entirely get. Some characters are more interesting than others, but that's inevitable when some of them are so interesting.

Amazon has the first few pages to read here.

If you've any interest in super heroes, popular culture, mutually assured destruction, morality, society, people, or just about anything else, then you should probably read Watchmen.

Postscript: I was talking to Mark the other week about the difference between the ending of the Watchmen film and comic. On the one hand, the ending of the film is significantly less mental. But on the other, it does significantly change the connotations of the ending. Which is more appropriate I couldn't say.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

rags to rags, riches to riches

I've been meaning to write about this for a while, but haven't got round to it until now.

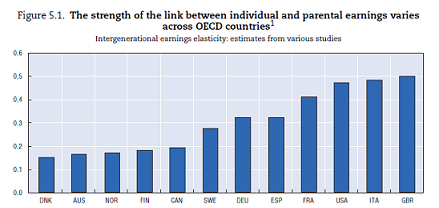

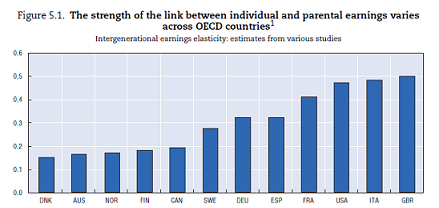

Last month The Guardian reported the finding of an OECD study that the UK has the worst social mobility of the dozen OECD countries for which data was available.

In economics, the basic measure of social mobility is how much someone's income is determined by the income of their parents, after controlling for certain variables. That's certainly not a perfect measure - for example it misses changes in income within people's lives - but it's hard enough to measure as it is. The OECD report also looks at the education, and its relationships with income.

This graph shows how much the income of parents determines the income of their children. The higher the score, the less social mobility there is. In crude terms, the rich stay rich, the poor stay poor. Most people wouldn't need persuading this is a bad thing. The UK is alongside Italy and the US in the difficulty poor children face getting richer, and the ease with which rich children stay rich. (Technically speaking, because of the limited accuracy of the measurements, we probably can't assert any real distinction between them.)

There are a few things I'd like to know more about. First is the influence of intra-generational inequality. The report does talk about this, and I think finds that inequality reduces mobility, but I didn't read it closely enough to understand exactly how, or how they accounted for this. Second, what is the effect of immigration? Migrant status is factored in in some way, but there's no discussion of how it might affect the findings. It may be of note that countries like the US and France have relatively high levels of immigration, Austria and Norway low. Thirdly, how does the size and heterogeneity of the US affect its figures? Eg. do people in poor states stay where they are, rather than making the (comparatively) distant move to a richer state to earn more money?

Those provisos aside, what struck me about this report was the same as other international studies of social mobility I've seen. It's a conventional view that the US is a land where anyone can make it big, that it is full of rags to riches (and riches to rags) stories, and more socially fluid than Europe. The actual evidence suggests otherwise. If you're born into a poor family in the US you're more than twice as likely to stay poor than someone in Denmark, or Canada. If you're born into a rich family, you're more likely to stay rich.

I'd like to have some useful insights for the UK, but unfortunately I don't. The report finds certain educational policies, plus redistributive and income support policies to strongly enhance mobility. If you're interested, have a skim of it yourself.

Last month The Guardian reported the finding of an OECD study that the UK has the worst social mobility of the dozen OECD countries for which data was available.

In economics, the basic measure of social mobility is how much someone's income is determined by the income of their parents, after controlling for certain variables. That's certainly not a perfect measure - for example it misses changes in income within people's lives - but it's hard enough to measure as it is. The OECD report also looks at the education, and its relationships with income.

This graph shows how much the income of parents determines the income of their children. The higher the score, the less social mobility there is. In crude terms, the rich stay rich, the poor stay poor. Most people wouldn't need persuading this is a bad thing. The UK is alongside Italy and the US in the difficulty poor children face getting richer, and the ease with which rich children stay rich. (Technically speaking, because of the limited accuracy of the measurements, we probably can't assert any real distinction between them.)

There are a few things I'd like to know more about. First is the influence of intra-generational inequality. The report does talk about this, and I think finds that inequality reduces mobility, but I didn't read it closely enough to understand exactly how, or how they accounted for this. Second, what is the effect of immigration? Migrant status is factored in in some way, but there's no discussion of how it might affect the findings. It may be of note that countries like the US and France have relatively high levels of immigration, Austria and Norway low. Thirdly, how does the size and heterogeneity of the US affect its figures? Eg. do people in poor states stay where they are, rather than making the (comparatively) distant move to a richer state to earn more money?

Those provisos aside, what struck me about this report was the same as other international studies of social mobility I've seen. It's a conventional view that the US is a land where anyone can make it big, that it is full of rags to riches (and riches to rags) stories, and more socially fluid than Europe. The actual evidence suggests otherwise. If you're born into a poor family in the US you're more than twice as likely to stay poor than someone in Denmark, or Canada. If you're born into a rich family, you're more likely to stay rich.

I'd like to have some useful insights for the UK, but unfortunately I don't. The report finds certain educational policies, plus redistributive and income support policies to strongly enhance mobility. If you're interested, have a skim of it yourself.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)